'Keyhole' Facilitation

‘Keyhole’ Facilitation is my approach to high-impact, low time-load strategy and leadership development work. Drawing on the medical metaphor of Keyhole Surgery, which is much less invasive that traditional ‘deep dive’ surgery, Keyhole Facilitation gets better results faster and easier.

A lot of the times when consultants and facilitators like me are brought into an organization to change something, the assumption is, from either side or both, that we need a lot of time to do things. I've spent months of my life on off-site retreats, hosting and participating, where we might spend a day, three, or a whole week to “deep dive” to look at our strategic future, or, design our organizational culture, unpack our implicit bias, or develop leadership acumen.

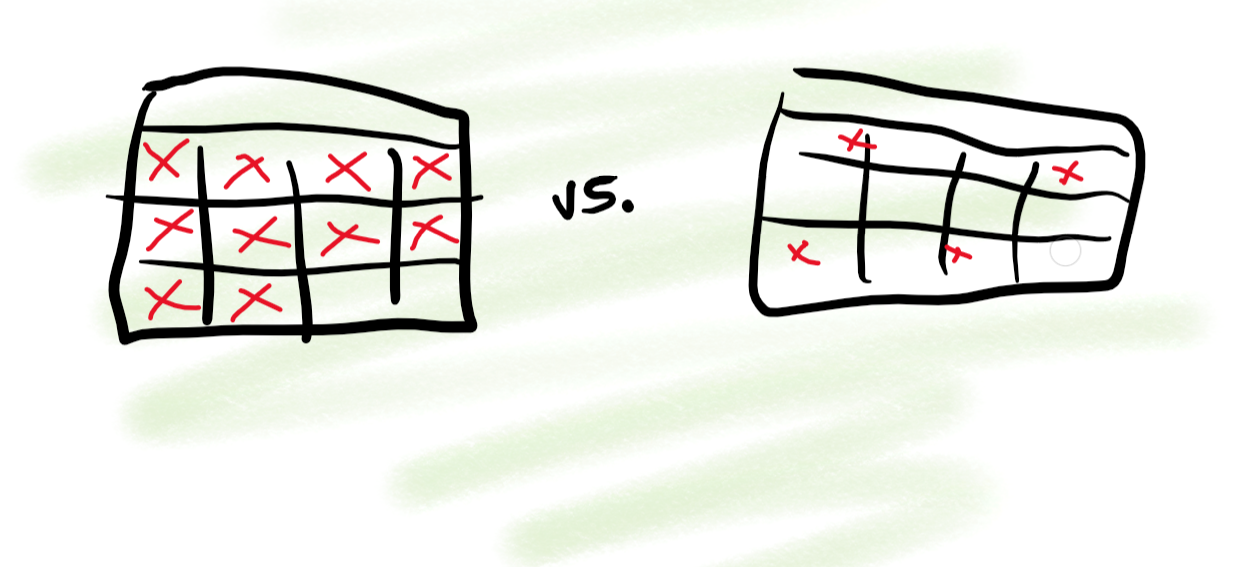

These ‘retreats’ can be highly effective, they can be inflection points for significant contributions and changes. They can be empowering and clarifying, enabling more and greater contributions from more people. But they are also a great way for a few people to get together to naval-gaze, feel self-important, and then carry on doing what they were always going to do. That's what I hear happens most often from clients who have worked with others before me. As a facilitator of this type of work it is frustrating to hear from others about such terrible processes and progress. Blunt and crude approaches that try to open everything up to solve everything. High cost, low value.

Last week I had Keyhole Surgery (nothing major, but my new advice is: don’t ski on East Coast Ice when you’re used to Colorado Powder), and it has made me think about the evolution of facilitated processes as being a bit like the evolution of surgery. There was a time when, if you ruptured a tendon in your shoulder, that would mean tearing open the whole shoulder and causing a whole lot of damage in order to repair some even worse damage. What follows is a lengthy recovery process that might leave you with a mostly-functioning shoulder that is, at least, better than it would have been if it hadn't been for the intense surgery but far from ideal or fully-functioning. These days, however, the advent of keyhole surgeries and other modern techniques can mean that only a tiny incision or three is required to do what has historically been an incredibly invasive procedure. In some cases a full recovery can be made to a shoulder that would have at other times been at best partially usable.

So what is ‘Keyhole’ Facilitation? The concept is, I would hope, fairly self-explanatory from the metaphor. How might we use a comparatively small amount of time and resources to create a lot of value and get us to a better and hopefully ideal position? It’s an idea and a practice that I’ve come to really love.

One of the weirder things I’ll say this week: organizations are a bit like shoulders. Every organization is different, but there's some common Anatomy in terms of people gathering to do things together for a particular purpose. There’s flow of resources, decision making, repeated actions... But the shoulder of a baby startup is very different from the shoulder of an elderly multinational corporation. The shoulder of an athlete in their 80s is different than that of a sedentary 80 year old, much like the strategy for a multinational for-profit Corporation would be different than that of a multinational not-for-profit, despite there being similarities by nature of them both being multinational. Diagnosing the need and the nature of the tensions and challenges at play is highly context and structure-dependent. They are also largely predictable, within reason. That's not to say the specifics aren't important, they always really really are, but also: knowing our own shoulder really well is a different thing to knowing what generally happens with shoulders. They’re both helpful in different ways.

A lot of people don't realize how often surgeries go wrong, have significant post operational issues, or are done erroneously (including removing the wrong limb). In recent years dramatic work has been put into and done by the international medical community to try and decrease the number of preventable errors to save stupid amounts of money and unnecessary suffering. Surgeon, writer, and public health researcher Atul Gawande wrote a fantastic book called “The Checklist Manifesto” about how using check lists can prevent surgical teams from accidentally leaving towels inside of people (my words, not his) because it turns out that surgical teams are people who make mistakes also. The main point of the book is simple: no matter how expert you may be, well-designed check lists can improve outcomes. Well designed check lists take what we know about the context, situation, people involved and common occurrences, then enable us to work through them in a simple fashion to save time and effort. It crosses t’s and dot’s i’s in the way that we know diet, sleep, and exercise are important, but forces us to actually do them before starting some other medication. Preparation and pre-planning, pre-thinking, and anticipation of unlikely-but-possible shit that might hit known-fans is a big part of doing effective modern surgery. It also means you don’t have to rip a whole shoulder open.

I recently tested this ‘Keyhole’ Facilitation approach with a mid-sized membership organization as I facilitated their annual strategic planning session. They didn’t know I was testing anything because they didn’t need to: they had a problem and wanted my help to fix it, and trusted me to find the best approach. And it worked! By directly naming the patterns across organizations like theirs, naming the wider context and current reality, and getting everyone across that in 3 pages of pre-reading before we met, we were able to immediately get down to the task at hand and process some gnarly stuff.

A week later I connected with the Executive Director to do a debrief - a bit of post-operative surgical care if you will - and the feedback says it all

“I am thrilled - I never thought that we would accomplish what we did, having been part of other several-day strategic plans. I am definitely more solution oriented, I wanted to cut through the crap and get to the answer, I was absolutely amazed.”

Here’s hoping my post-operation follow up is this positive!

What is Positive Psychology Coaching and why is it helpful?

Every one of us sees the world from one perspective only - our own eyes. A skill developed by many great people is that of perspective taking - seeing the world as if from the eyes of another. Emotional intelligence relies on our ability to to see things from others perspectives, and to manage our own emotions accordingly, and it’s one of the clearest hallmarks of an effective leader.

In order to do really any of this at any level of sophistication, we have to appreciate that our perspective of the world is not a perfect view. We each bring our own interpretations, bias, assumptions, and values to the ways we see the world. These have, in turn, shaped the ways that we understand the world. It drives all of our habits and patterns of behavior - for better or worse. It’s like looking at the world through rose-tinted glasses - we have to recognize the tint of the rose and account for it when understanding what we see through them.

One of the ways we can better understand our brains is through Positive Psychology tools. Think of psychology as having two broad branches. One is the study of disorders: things that go ‘wrong’ with our brains, our behavior, thoughts, and feelings. This is what many of us typically picture when we think about ‘a psychologist’ - someone who ‘helps us fix things that have gone wrong with our brains’.

The other broad branch is the study of things that are ‘right’ with the brain. Rather than looking at problems or shortcomings, it’s more about looking at superpowers and capabilities. Positive psychology is the study of natural inclinations and tendencies, sometimes also called talents, strengths, aptitudes, etc.. Some of us can easily remember the names and faces of people we met only once years earlier, while others struggle to remember the name of the person who just introduced themselves a few minutes ago. Some people can easily adapt to unexpected changes in a day, rearranging their lives with little effort and low stress, while others can feel thrown into total disarray by unexpected changes. Some people like taking risks, others do not. We are all born with capabilities that show up very easily for us and we often don’t realize they are hard for others.

Positive psychology tools and assessment are designed to help people get a snapshot of how their brain is wired, the tint of their rose glasses if you will. With an understanding of these tendencies we can start to describe ourselves to ourselves. E.g.

I tend to find it easy to remember names and faces.

I tend to struggle when my plans change unexpectedly.

I’m inclined to take risks.

I’m inclined to say yes when someone asks for help.

Sitting in behind each of these tendencies or inclinations is the complex web of activity in our brains. It can relate to our skills, experiences, sense of self, our beliefs about ourselves, concepts of what is ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ etc etc. Trying to better understand these inclinations and tendencies is the work of Positive Psychology.

It’s important to highlight that the results of these self-assessments are not necessarily 'the truth' or 'right'; instead they are a reflection of how you understand yourself. Just like how a map is not the same thing as the terrain it represents, the results of these assessments are not necessarily the terrain of your mind. They can help you explore your mind, but the maps alone cannot necessarily give you answers of what’s actually happening.

Just like how terrain can have pitfalls and cliffs, so too can our natural inclinations. A natural tendency to take risks can be very helpful in some contexts, and very damaging in others. As can a natural inclination to help others. Left unchecked, our natural inclinations can lead to patterns of bahavior in our lives or relationships that don’t serve us or the people around us very well. For many, positive psychology tools can cast a new light persistent challenges in their lives - turning perceived ‘weaknesses’ into new sourced of strength.

Working with a positive psychology coach can be a profoundly beneficial thing for a lot of people, as it gives them insight into and language for things that they often know about themselves but haven’t been able to really understand or make sense of. Learning new skills or shaking off old habits is often made easier - it’s a bit like building a new structure with a clear view of the ground where it was previously hidden.

What 'Thankyou' means for social enterprise in NZ

*** Edit: After a chat with the *very friendly* team at Thankyou HQ I’ve made a small amendment to descriptions of Thankyou’s social enterprise model and added more things I like about them. I had previously described Thankyou as having a ‘one-for-one’ approach, yet this is not technically correct so now amended. ~J ***

Recently Australian Social Enterprise Thankyou launched into New Zealand with their line of everyday consumer items where 100% of profits are used to fund impact projects. Their arrival pushed social enterprise well and truly into the centre of mainstream media for a few days, with charismatic co-founder Daniel Flynn showing up on Radio NZ, The Project, The AM Show, and idealog to name a few. Not to mention their personal care items being available online and in heaps and heaps of supermarkets and stores around the country!

Thankyou is one of those amazing brands that people just love. It is a consumer movement that leverages extreme consumerism to tackle extreme poverty. Flynn's book Chapter One describes to some depth the lengths that their (many thousands of) supporters went to supporting Thankyou to launch in Australia. The highlights reel includes helicopters with signs and volunteer flashmobs, with most of the best stories coming from their campaign to get supermarket chain Coles to stock Thankyou Water - where every bottle sold funds water and sanitation projects elsewhere in the world.

The arrival of Thankyou is a significant milestone in the story of social enterprise in New Zealand. We now have well-known media personalities actively promoting and talking about social enterprises, let alone understanding what they are. This is about as exciting as it was having Suzy Cato walk out to MC the Social Enterprise World Forum (which was amazing, in case you weren't there). Social enterprise has well and truly landed in New Zealand!

I will always buy a Thankyou product over a traditional competitor, and as a social enterprise practitioner and teacher I am also a fierce critic of Thankyou. There are many wonderful things to celebrate about Thankyou, and there are also significant flaws to their approach and their model - so they are not a good role model for aspiring or emerging social enterprises. There are many other leaders of social enterprises in New Zealand who are also critical of Thankyou (for reasons I'll go into in a moment), and several of them have had push-back from friends and colleagues for being 'haters' or 'tall poppy'. So I'm here as an ally for them, and to drive the conversation for more and better social enterprises in New Zealand.

Buy Thankyou products and tell your friends about them.

What works about Thankyou

To date, the impact made is considerable and impressive, and every item sold has a unique ID that lets you track your impact directly to where in the world you are helping. As of May 2018 their community (Thankyou + customers) have contributed:

- $5.8 million to fund water access, sanitation & hygiene for 785,000 people

- 8,563 water, sanitation, and hygiene solutions for 866 communities in 17 countries

- Child and maternal health solutions for 94,477 mums and bubs

As you can tell, they have a really clear idea of the big needles they are trying to move:

- 844 million people around the world don’t have access to safe water

- 2.4 billion people don’t have access to safe toilets

- It is estimated that 96 people per hour are dying from preventable waterborne diseases

- 2.7 million babies don’t make it through their first month of life every year because they don’t have access to basic health care

- a mother dies every 103 seconds due to pregnancy and childbirth related issues, with 99% of these deaths occurring in developing countries

As a set of impact metrics and measurable and meaningful problems, these are impressive. All of their impact initiatives align with the Sustainable Development Goals too, which is necessary. Understanding the actual problem they are trying to solve is the number one thing that most social enterprises do poorly, and Thankyou doesn't fall into this trap, which is excellent.

In addition to this clear understanding of problem and clear impact reporting, Thankyou does one other thing really well: helping everyday people see the possibilities of social enterprise. Every product sold shares a theme with the impact it is having, so the sales of western consumer products around e.g. babies fund solutions in emerging economies related to babies and childbirth. Their impact is essentially outsourced - they form charitable partnerships with those who work internationally, leaving Thankyou to build a brand and movement that makes money. They talk about leveraging extreme consumerism to tackle extreme poverty. New customers are exposed to the idea that everything we buy could be adding value to the world. Being a (relatively) large brand, the reach of their products will probably outstrip every existing social enterprise campaign in New Zealand. Woop! Their arrival and related media and brand awareness pushes social enterprise awareness in NZ onto a doubling curve. Which. Is. GREAT!

Recognising and acknowledging these great things, lots of social enterprise practitioners are both supportive and critical of Thankyou, which I believe is healthy and productive. We know that there are more unmet needs than solutions, and robust debate can help those of us who care to improve our own thinking and solutions. Such conversations shouldn't involve throwing stones or interrupting other people's approaches to solving social or environmental challenges. In those cases, no one wins. Critical conversations should be about the merits and shortcoming of approaches and models, with a view to learning and improving all of our understanding and practice. That is, how can we solve more social and environmental challenges in more ways, more often.

What doesn't work about Thankyou

I challenge Thankyou because of the way that they make money and it's unintended consequences, and the way that they talk about how they started.

Bottled water is of course a dumb product, especially in New Zealand where just about every public tap pours out world-class drinking water. This was part of the reason why water wasn't the first item launched into New Zealand, and they instead started with their personal care line which will soon be followed by their baby-related items.

Put simply, most Thankyou products solve one problem whilst creating or perpetuating others. The oft-defended rationale is that 'at least this bottled water/disposable nappy/wet wipe is making the world a better place' - we would rather someone buys something like bottled water from Thankyou than from, say, Coca Cola. This is totally valid, totally short-term, and totally defeatist. It either concedes that extreme consumerism is here to stay so we should work with it, OR, is setting up to be a gateway drug that helps customers go on a journey away from single-use disposable items and towards less consumption in general. I really hope Thankyou is doing the latter, but they've never submitted anything about banning single-use plastics or similar systemic interventions, so it seems unlikely. We can do better, and social enterprises that are really committed to moving the needle ARE doing better. Happy to write about some of them if asked.

My second criticism is the way that Thankyou celebrates and promotes their start up journey. The short version is that 3 passionate, eloquent, well educated young Australians heard the gnarly stats about water and sanitation internationally, heard the money spent on water in Australia, and then worked for free for three years to start a bottled water company fully owned by a charity. They were constantly told 'it won't work' and their war cry became 'What if it does work?'. Despite all odds they were successful, and several years and thousands and thousands of hours and free goods and services later, they made their first donation.

In the business of starting impact initiatives, running off and doing a whole bunch of stuff for many years with the hope that maybe one day you will make an impact is the number one thing you should not do. And that's exactly what Thankyou did and promotes. What we have in New Zealand is the highest number of not-for-profits per capita in the world, and some of the worst stats in the world for things that the majority of not-for-profits exists to solve. We have too many people doing things and hoping they will make an impact down the line, which continues to not eventuate.

As a role model and case study for how to start a social enterprise, Thankyou might just be one of the very worst approaches that someone could take in terms of building a business focused on actually making an impact, but it's one of the best case studies of a brand raising awareness and growing a consumer movement. That's why they're so successful - they make us feel like we're making a bigger impact than what we perhaps are.

What could they have done differently?

There are a few different ways that Thankyou could have approached their social enterprise start up journey, and a few things they could have done differently within the approach that they took. A social enterprise is constantly optimising the relationship between it's business model (where and how money is earned) and it's impact model (where and how the good happens), and there are a few ways that these two models can relate. What emerges as a result of the relationship between these two is what is called their 'social enterprise model'. Across all models, the approach I personally recommend involves rolling things out step by step, and with each step making a positive dent, learning something specific, and (preferably but not always) making some money. If we fail, at least we've done some good. If we succeed, we'll do a lot more. A critical part of this process is understanding and actively watching for unintended negative consequences - which TOMS shoes learned about the hard way. (Incidentally, TOMS are undertaking a change in their whole model, having moved internally towards a product innovation model but keeping their brand proposition of ‘buy-one-give-one’ after learning a lot on their incredible start up journey.)

But there are other approaches too.

Thankyou's approach was to 'make money over here, and do some good over there' - what's called a 'resource generation model' of social enterprise. Better approaches to this model would make money in a way that doesn't add to other problems in the process (that’s a polite way of saying that bottled water may have been a bad choice). Such approaches are where someone takes an existing business idea, audits all the negative externalities of the business, then builds a different version without the bad stuff. For example, imagine that someone sells body care items: you'd see that animal testing, synthesised ingredients with harmful side effects on humans, unsustainably sourced ingredients, high water use, plastic packaging, and multi-wrap plastic packaging that can't be easily recycled is a quick hit list of bad things; and then make body care items without any of them. Sound hard? It is. It isn't common because it turns out that it's easier to make a mess than to keep things clean. Despite the obvious challenges, this is exactly how Malcolm and Melanie Rands started Ecostore, now well known for making body care products 'without all the nasty chemicals'. They even spent two decades trying to work around the need for plastic, which they managed to do through the invention of the amazing Carbon Capture Pak - which you should probably read about right now. Ethique took this exact same thinking one step further by not having any plastic, or any water, or any of the other bad stuff - their body care line are all solid bars that are delivered to your door wrapped in paper and cardboard. Hard, and totally doable. The competitive edge that the Rands' and Ethique's Brianne West had is that they were doing things that are deeply authentic to them as individuals - the former living in an ecovillage and the latter being a chemist. It's easy to come up with an idea, but it's harder to develop deep understanding and expertise in something - and that's why 95% of businesses, charities, and social enterprises fail.

Consider if Thankyou had taken what they're really authentic and good at (inspiring consumer movements and forming strong partnerships) and rolled that into New Zealand by partnering with Ecostore and/or Ethique. Multinational organisations are often successful because of their ability to align their supply chains and products, whilst diversifying their brands and marketing. Why not do that? These types of collaborations require all parties to recognise that on the surface they are competitors, but underneath they are all committed to something much bigger than each of them (be it profit or impact). This approach of coopetition (cooperative competition) is exactly what's needed of impact-led organisations if they are going to out-perform existing global monoliths. All it takes is an authentic desire to do good, an open mind, and some sound business acumen. Handily, these are also the main ingredients for running a social enterprise.

Closing thoughts

The arrival and fanfare surrounding Thankyou's arrival provides a great context and awareness for many more people to join existing social enterprises and start new ones.

It's easy to point at products like body care items above and pull apart the business model and rebuild it in an environmentally sustainable way - very easy in concept, very hard in practice. It's even harder to do the same when you look at a business through the lens of The Treaty of Waitangi or institutional sexism, or consider a businesses' role in contributing to domestic violence or drug and alcohol abuse. These are but some of the gnarly challenges that we have to work through in New Zealand, and there simply aren't answers yet to many of these things. We know prevention is better than response (just like not using plastic in the first place is better than recycling it), but both are currently still needed for most social and environmental challenges. Solving a problem usually requires a lot more understanding of the problem than it does designing of the solution. What's the problem that the social enterprise ecosystem is solving in New Zealand?

The opportunity we have in Aotearoa New Zealand is to find and celebrate role model organisations that apply the type of thinking that built Ecostore and Ethique, who also move needles on these other very real social issues. Imagine the impact if every young person inspired by Thankyou was trying to build one of those, instead of spending years and years making plastic to hopefully one day make impact in other ways.

The reality is that doing social enterprise well is really hard. And that's ok. Doing it well en masse is something that hasn't really been done globally - no country has really figured out how to do this stuff properly yet. That's the role that the New Zealand social enterprise ecosystem could take: aspiring for each organisation to solve one issue as part of a coherent ecosystem that challenges and supports each other to solve each and all of the issues. This is what I'm striving for with the team at Felt, and what I support many other orgs to do in the various programmes I'm involved with designing and teaching.

As an emerging sector, we need to have mature discussions about what works and what doesn't, and to get collective understanding on what counts as 'good' outside of what counts as 'charitable'. Simply doing that will put us leagues ahead of many other places in the world, and we're lucky that the ecosystem is small enough and connected enough that we can still do it in New Zealand. I hope that we can do that before the ecosystem gets too big.

Maybe that can be a '1 year post SEWF' conversation? Or maybe you've got thoughts to add below?

Collective Impact

Collective Impact is a methodology that enables multiple organisations to work together to tackle complex, often unresolved, social and environmental challenges, often over multi-year initiatives. The language of collective impact was first proposed in 2011 through a Stanford Social Innovation Review Paper, which started somewhat of a revolution globally. Collective Impact has since evolved considerably thanks to enormous numbers of projects all over the world using the framework to varying degrees of success.

In New Zealand we have some strong examples of collective impact, particularly in kaupapa māori contexts. I'm personally involved with three collective impact projects, and have co-written a research paper on the evolution of collective impact for Aotearoa, with a supporting infographic on this evolution and opportunities moving forward.

I'm a proponent of ideas proposed by the Tamarack Institute in their paper Collective Impact 3.0, which has been very influential on my thinking for social enterprise and organisational design also. In this framing, collective impact utilises a movement-building mindset to enable multiple players to work together in pursuit of shared desired outcomes even if or when they are competing with one-another. Collective impact is best suited for complex, often unresolved, social and environmental challenges where there is no 'best practice' or even 'good practice' solution - think child poverty, consumer plastic addiction, social enterprise sector establishment, mental illness, homelessness and related challenges…

The core ‘ingredients’, known as the ‘Five Conditions of Collective Impact’, speak to both a high-trust environment and a deep collective desire to exert change:

The Five Conditions of Collective Impact 3.0

1. Shared Community Aspiration

Common overarching desired outcome, backed up by individual organisational understanding of their more specific desired outcomes and roles in contributing to the overarching outcome.

2. Culture of Strategic Learning

A culture of driving progress towards outcomes as the main priority, emphasising the sharing of key lessons across all players and a minimum of traditional output reporting and compliance as strictly necessary. Recognises the difference between contribution and attribution.

3. High Leverage Activities

Designing operations to support and maximise the impact of each others work, striving for multiplier effects wherever possible. This speaks of deep operational collaboration and information sharing.

4. Inclusive Community Engagement

Open and inclusive approaches to identifying desired outcomes, tracking progress and learning, and growing and improving services. Including ‘real people on the ground’ at all stages, ongoing.

5. Containers for Change

Supporting infrastructure to facilitate the ongoing inclusion, learning, and change within and across organisations. Holding a space where participants are supported and challenged enough to work together.

I'm always happy to discuss collective impact with anyone who thinks they may be already working on something similar to this, or who thinks it would be helpful.